Decisions and communications you make will alter patient perspective

Idyllwild, CA – June 1, 2016 – by Kasaan Hammon

In an age of WebMD and Google, patients come to a doctor’s visit more often than not with preconceptions about what their symptoms mean, a list of multiple concerns which they want to address in one visit, and often a history of treatment for chronic illness which may or may not have been effective. In other words, they are loaded up with information, experience, and expectations. What is the doctor’s role then? How can doctors meet patients’ expectations and involve them actively and effectively in their own care while still maintaining their authority as medical professionals? The key may be in appropriately factoring in the patient perspective.

Dr. Gurpreet Dhaliwal, an associate professor of clinical medicine at the University of California San Francisco and a staff physician at the San Francisco VA Medical Center, puts it this way: “Doctors can improve their communication by seeking to understand the perspective of the patient. This critical duty can be simplified by always asking patients three simple questions (I.C.E.): Idea—What is your idea about what is going on? Concerns—What are you most worried about? Expectations—What are you expecting that I can do? When the doctor understands what the patient believes, fears and wants, they can both ‘get down to business’—the business of healing the body and the mind.”(1)

This involves empathy, but there is a distinct difference between clinical empathy and emotional empathy. Clinical empathy is understanding a patient’s emotions, as opposed to emotional empathy (or sympathy), which is sharing a patient’s emotions. Sympathy can hinder objective diagnoses and effective treatment. Dr. Helen Riess, founder of Empathetics, explains: “Sympathy often leads to prosocial behavior, but it can also lead to misguided decisions. In contrast, cognitive (clinical) empathy is understanding what the person feels and thinks, regardless of whether you have been in the exact same situation or whether you feel the person’s emotions. Our role as physicians is to get under the patient’s skin and see the world from their point of view, but also to get back out so that we can be objective and make the best rational decision.”(2)

Research has shown that many patients prefer a shared decision-making model which includes their perspective.(3) Integrating the patient perspective has the potential to increase the patient’s satisfaction with the consultation, lead to better adherence to medications, lower the likelihood of mistakes, and result in fewer malpractice cases. It even affects patient health outcomes; a review of research concluded that effective physician-patient communication improves patients’ emotional health, symptoms, physiologic responses and pain levels.(4)

However, hearing the patient’s perspective involves time, and the looming pressure of time constraints are a key issue in today’s consultations. Doctors are often guilty of interrupting a patient to control the length of the visit. A study found that in 7 out of 10 office appointments, doctors interrupted before patients could finish explaining their health concerns.(5) The pressure is on doctors to come up with diagnoses and treatment plans quickly, while a patient’s satisfaction with the visit is dependent upon feeling heard.

The solution to this conundrum may just be a matter of keeping the “effective” in communication. With no additional time spent, effective listening and tuning in to non-verbal cues can vastly improve the quality of communication. UCLA research has shown that only 7% of communication is based on the actual words we say; 38% comes from tone of voice; and the remaining 55% comes from body language.(6)

Dr. Travis Bradberry gives eight tricks for reading body language: 1. Crossed arms and legs signal resistance to your ideas; 2. Real smiles crinkle the eyes; 3. Someone copying your body language is a good thing; it means they feel a bond or are on the same page with you; 4. Maintaining good posture commands respect and promotes engagement; 5. People who are lying may overcompensate and hold eye contact to the point that it feels uncomfortable; 6. Raised eyebrows signal discomfort and feelings of surprise, worry or fear; 7. Exaggerated nodding signals anxiety about approval; and 8. A clenched jaw signals stress. “What can be most important to read is when words and body language don’t match,” says Dr. Bradberry.(7)

Patients feel more understood when doctors practice active listening. This includes smiling and nodding the head, eye contact, leaning slightly forward or tilting the head sideways while listening, automatic (not forced) reflection or mirroring of any facial expressions used by the speaker, and avoiding distraction. When exercising verbal reflection, casual and frequent use of words and phrases such as ‘very good,’ ‘yes’ or ‘indeed’ can become irritating to the speaker. It is usually better to elaborate and explain why you are agreeing with a certain point.(8)

While empathy courses are not currently required in medical training, interest in them is growing.(9) Columbia University School of Medicine has pioneered a program in “narrative medicine,” which emphasizes the importance of understanding a patient’s life story and value system when providing compassionate care. A range of “medical humanities” courses incorporate philosophy, film, art, and literature to enhance healthcare workers’ reflective practice and observational skills.(10)

At the end of the day, patients are looking for empathy, engagement, and shared decision-making. Researcher Zanini writes, “In the age of information, patients form their views outside the medical consultation, and these views can facilitate or hinder any collaboration with doctors. For patient informed care to take place, doctors need to identify and address the patient perspective.”

(1) Gurpreet Dhaliwal; “Ask Patients These Three Simple Questions;” Wall Street Journal, April 2013; (2) Kasley Killam; “Building Empathy in Healthcare;” syndicated from Greater Good, January 2015; (3) Claudia Zanini; “Doctors’ Insights into the Patient Perspective: A Qualitative Study in the Field of Chronic Pain;” BioMed Research International, May 2014; (4) Stewart MA; “Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review.,” CMAJ, May 1995; (5) Beckman MD and Frankel PhD; “The Effect of Physician Behavior on the Collection of Data;” Academia and the Profession, November 1984; (6) A. Mehrabian; “Silent messages: Implicit communication of emotions and attitudes;” Wadsworth, 1981; (7) Bradberry MD; “8 Great Tricks for Reading Body Language;” Huffington Post, May 2016; (8) “SkillsYouNeed.com”; (9) Sandra Boodman; “How to Teach Doctors Empathy;” The Atlantic, March 2015; (10) Eric J. Hall; “Why We Need the Humanities to Improve Health Care;” Huffington Post, July 2014.

In-House Scribe SolutionsTake control of your medical scribe program

In-House Scribe SolutionsTake control of your medical scribe program Contracted Full-Service Scribe SolutionsWe Build a Turn-Key Scribe Program For Your Organization

Contracted Full-Service Scribe SolutionsWe Build a Turn-Key Scribe Program For Your Organization In-House Scribe SolutionsTake control of your medical scribe program

In-House Scribe SolutionsTake control of your medical scribe program In-house Scribe Program OverviewWith the ScribeConnect Scribe Management Platform you can have the best part of medical scribe’s EHR documentation help right in your organization.

In-house Scribe Program OverviewWith the ScribeConnect Scribe Management Platform you can have the best part of medical scribe’s EHR documentation help right in your organization. Overview and Key featuresMedical scribe management doesn’t have to be difficult, no matter what every other scribe providers tell you. The only SaaS medical scribe management platform is here for you.

Overview and Key featuresMedical scribe management doesn’t have to be difficult, no matter what every other scribe providers tell you. The only SaaS medical scribe management platform is here for you. for Healthcare OrganizationsFrom large hospital systems across urban centers, to small clinics operating in rural areas, our platform is designed to scale, grown, and accommodate your medical scribing needs.

for Healthcare OrganizationsFrom large hospital systems across urban centers, to small clinics operating in rural areas, our platform is designed to scale, grown, and accommodate your medical scribing needs. for Education InstitutesLooking for ways to offer your pre-med and pre-PA students more value? Or have a scribe training curriculum already in place and looking for a wider medical student audience? We can help.

for Education InstitutesLooking for ways to offer your pre-med and pre-PA students more value? Or have a scribe training curriculum already in place and looking for a wider medical student audience? We can help. for Scribe ApplicantsApply to medical scribe job openings across the country, and join a community of thousands of medical scribes. Access our comprehensive scribe training courses and more!

for Scribe ApplicantsApply to medical scribe job openings across the country, and join a community of thousands of medical scribes. Access our comprehensive scribe training courses and more! How to use our PlatformOur platform is simple to use, with robust features and powerful tools. Learn how to get the most out of our SaaS based platform with tips and tricks.

How to use our PlatformOur platform is simple to use, with robust features and powerful tools. Learn how to get the most out of our SaaS based platform with tips and tricks. Contracted Full-Service Scribe SolutionsWe Build a Turn-Key Scribe Program For Your Organization

Contracted Full-Service Scribe SolutionsWe Build a Turn-Key Scribe Program For Your Organization Full-Service Scribe Program OverviewWe hire, train, and manage your medical scribes so you don't have to.

Full-Service Scribe Program OverviewWe hire, train, and manage your medical scribes so you don't have to. Any provider, any time, anywhere.ScribeConnect has provided full-service, turn-key medical scribe programs for healthcare organizations large and small.

Any provider, any time, anywhere.ScribeConnect has provided full-service, turn-key medical scribe programs for healthcare organizations large and small. Frequently Asked QuestionsHere are some frequently asked questions that may help you decide whether or not a medical scribe program is right for you.

Frequently Asked QuestionsHere are some frequently asked questions that may help you decide whether or not a medical scribe program is right for you. Healthcare OrganizationsOur platform empowers your organization with intuitive tools to recruit, track applicants, train & certify scribes, and manage teams. Build and grow a strong and dynamic scribe program of any size with confidence.

Healthcare OrganizationsOur platform empowers your organization with intuitive tools to recruit, track applicants, train & certify scribes, and manage teams. Build and grow a strong and dynamic scribe program of any size with confidence. Healthcare OrganizationsOur platform empowers your organization with intuitive tools to recruit, track applicants, train & certify scribes, and manage teams. Build and grow a strong and dynamic scribe program of any size with confidence.

Healthcare OrganizationsOur platform empowers your organization with intuitive tools to recruit, track applicants, train & certify scribes, and manage teams. Build and grow a strong and dynamic scribe program of any size with confidence. Solutions For Your Healthcare OrganizationEase your documentation load, keep your providers happy, and improve your revenue cycle with ScribeConnect Medical Scribe Solutions. Designed for Healthcare Networks, Clinics, Hospitals, Emergency Departments, and Practice Management Groups

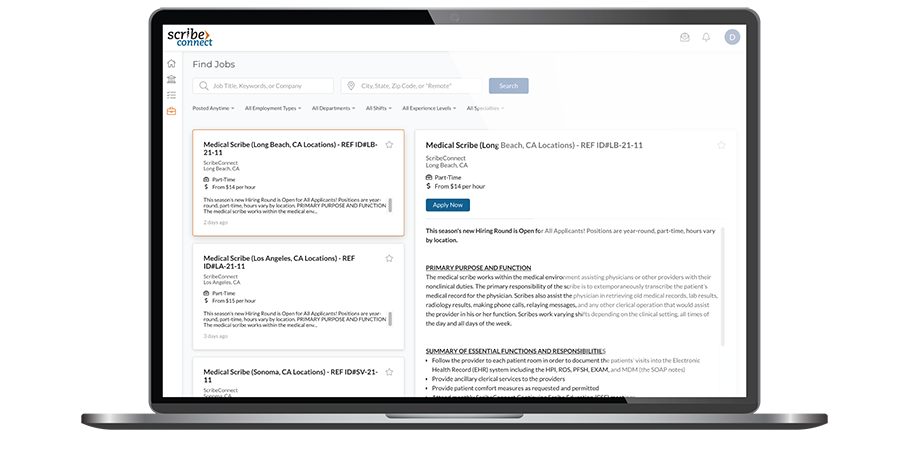

Solutions For Your Healthcare OrganizationEase your documentation load, keep your providers happy, and improve your revenue cycle with ScribeConnect Medical Scribe Solutions. Designed for Healthcare Networks, Clinics, Hospitals, Emergency Departments, and Practice Management Groups Post A Job & Track ApplicantsWhether you're hiring one scribe, or an entire team or teams of scribes, we have America's largest dedicated medical scribe job board. Post, manage, and HIRE the most qualified scribes.

Post A Job & Track ApplicantsWhether you're hiring one scribe, or an entire team or teams of scribes, we have America's largest dedicated medical scribe job board. Post, manage, and HIRE the most qualified scribes. Course CatalogOur industry-leading, academically-based, professional Medical Scribe Training Courses (MSTCs) are designed for a range of topics, from general and continuing scribe training to in-depth specialty-specific courses.

Course CatalogOur industry-leading, academically-based, professional Medical Scribe Training Courses (MSTCs) are designed for a range of topics, from general and continuing scribe training to in-depth specialty-specific courses. Educational InstitutionsFrom enrollment to alumni services, ScribeConnect’s platform can be your powerhouse medical scribe training and certification program.

Educational InstitutionsFrom enrollment to alumni services, ScribeConnect’s platform can be your powerhouse medical scribe training and certification program. Educational InstitutionsFrom enrollment to alumni services, ScribeConnect’s platform can be your powerhouse medical scribe training and certification program.

Educational InstitutionsFrom enrollment to alumni services, ScribeConnect’s platform can be your powerhouse medical scribe training and certification program. Academic PartnershipsSee what a partnership with ScribeConnect can do for your department and institution.

Academic PartnershipsSee what a partnership with ScribeConnect can do for your department and institution. Learn About Our Collegiate CoursesLearn about our academically-rigorous certificate courses that have been developed for the college student and how they can complement & expand your program's offerings.

Learn About Our Collegiate CoursesLearn about our academically-rigorous certificate courses that have been developed for the college student and how they can complement & expand your program's offerings. Financial Partnership ProgramSee how our financial partnership program can provide your institution with a new income stream in an extremely fast-growing, emerging, and competitive industry.

Financial Partnership ProgramSee how our financial partnership program can provide your institution with a new income stream in an extremely fast-growing, emerging, and competitive industry. ScribesAspiring scribes begin their education and path to employment here, while experienced scribes can learn valuable new skills and specialty-specific knowledge to take it to the next level.

ScribesAspiring scribes begin their education and path to employment here, while experienced scribes can learn valuable new skills and specialty-specific knowledge to take it to the next level. ScribesAspiring scribes begin their education and path to employment here, while experienced scribes can learn valuable new skills and specialty-specific knowledge to take it to the next level.

ScribesAspiring scribes begin their education and path to employment here, while experienced scribes can learn valuable new skills and specialty-specific knowledge to take it to the next level. What We Can Do For YOU?ScribeConnect has built a rich legacy of helping pre-medical professionals launch their careers. Now we're providing more powerful tools than ever before to help you win. See how.

What We Can Do For YOU?ScribeConnect has built a rich legacy of helping pre-medical professionals launch their careers. Now we're providing more powerful tools than ever before to help you win. See how. Find JobsSearch our job board and apply to jobs in your area. Apply to work directly with ScribeConnect at one of our locations or apply directly to one of our partners.

Find JobsSearch our job board and apply to jobs in your area. Apply to work directly with ScribeConnect at one of our locations or apply directly to one of our partners. Course CatalogPosition yourself above the competition when you get certified through our rigorous Medical Scribe Training Courses (MSTCs). You'll be prepared and equipped to work as a scribe in the medical setting of your choice.

Course CatalogPosition yourself above the competition when you get certified through our rigorous Medical Scribe Training Courses (MSTCs). You'll be prepared and equipped to work as a scribe in the medical setting of your choice.